Day 9.

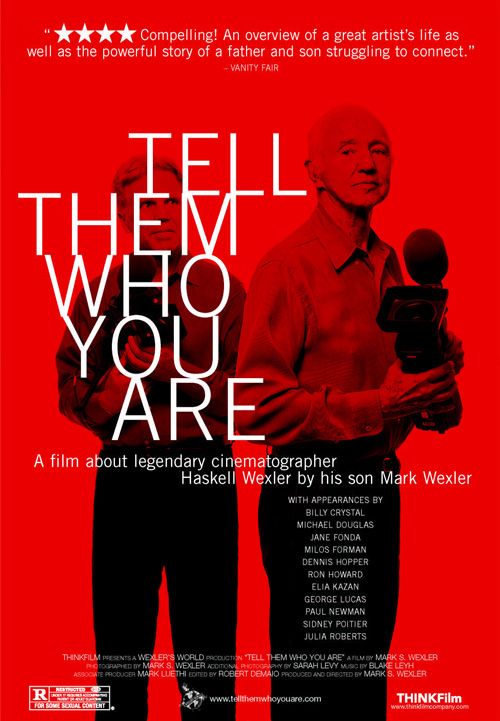

It’s amazing how the ending of a film can totally change your perspective of the entire work. Going into Tell Them Who You Are, I had only watched the opening scene in a film class and didn’t know who Haskell Wexler was. By the end of the movie, I felt as if I had an accurate portrait of the Hollywood legend.

It’s amazing how the ending of a film can totally change your perspective of the entire work. Going into Tell Them Who You Are, I had only watched the opening scene in a film class and didn’t know who Haskell Wexler was. By the end of the movie, I felt as if I had an accurate portrait of the Hollywood legend.

Mark Wexler, the son of the Oscar-winning cinematographer, wanted to make a documentary about his father. In a boring amateur opening that Mark narrates, the viewer is given an overview of Haskell‘s work through images and interviews with Hollywood heavyweights like George Lucas and Ron Howard. It is due to his father’s suggestion that Mark not make a biography with a focus on his body of work, but rather focus on their father-son relationship and his personal life, that Tell Them Who You Are is born.

Haskell Wexler makes this film, in the literal sense. Mark’s narration (and his actual voice) is annoying because it spoon feeds the viewer what is happening. He even includes a talking head interview that provided the title of the film. Maybe I’m an unknowing supporter of direct cinema because I feel, like Haskell and Albert Maysles, that the best documentaries are those that capture moments of genuine humanity. While I did get a sense of Haskell‘s overpowering, direct, confrontational, and political activist personality from his interactions with his son, many of the film’s interviews felt unnecessary, almost a sort of look at all these awesome famous people I got to interview. It seemed to follow the standard documentary formula, interview some people who know the subject and show the subject doing daily activities, without inspiration.

It is only during the last third of the film that the film seems to begin fulfilling it’s purpose and start to come together. Hearing Haskell‘s harsh comments to Mark showed that they didn’t have the best relationship and he certainly wasn’t an endearing father. He clearly was a bit egotistical and wanted to be the only filmmaker in the family; nonetheless, I didn’t dislike him because, as Jane Fonda states, he loved his son. Maybe it’s because my own grandfather is of Haskell‘s generation that I understand where he was coming from. Showing emotion as a man was not looked upon favorably in his day, so instead of apologizing, in my opinion, Haskell hoped to use this film to atone for his past mistakes. A kind of catharsis. There is one scene where Haskell says, in an apparently joking manner, that if he had Mark focus on mental and physical exercise he wouldn’t have turned out to be “such a mess.” I could be making excuses for him, but I took his sometimes harsh words about Mark as his way of expressing his disappointment that he wasn’t a better father.

It is only during the last third of the film that the film seems to begin fulfilling it’s purpose and start to come together. Hearing Haskell‘s harsh comments to Mark showed that they didn’t have the best relationship and he certainly wasn’t an endearing father. He clearly was a bit egotistical and wanted to be the only filmmaker in the family; nonetheless, I didn’t dislike him because, as Jane Fonda states, he loved his son. Maybe it’s because my own grandfather is of Haskell‘s generation that I understand where he was coming from. Showing emotion as a man was not looked upon favorably in his day, so instead of apologizing, in my opinion, Haskell hoped to use this film to atone for his past mistakes. A kind of catharsis. There is one scene where Haskell says, in an apparently joking manner, that if he had Mark focus on mental and physical exercise he wouldn’t have turned out to be “such a mess.” I could be making excuses for him, but I took his sometimes harsh words about Mark as his way of expressing his disappointment that he wasn’t a better father.

I was hoping that Mark would experience more of a transformation during the film. I wanted him to stop being so guarded and have a real conversation with his father about the issues he had with him. Whenever the topic of their father-son relationship was broached, Mark become more shelled in and tried to laugh it off. The film would’ve been better if he voiced his opinions of his father in a more genuine and authentic way. It is because Mark‘s reservation, which greatly contrasted Haskell‘s honesty, that I didn’t feel bad for Mark, even when his father did say hurtful things. I admit that this is also probably because I liked Haskell and could kind of relate to his liberal outspoken personality, even though I’m sure he was difficult to work and live with. I sometimes wonder how I’ll react if my kid is conservative like Mark Wexler, or even worse a follower. Hopefully I won’t be as bad as Haskell.

This film has the honor of having the most emotional and heartbreaking scene that I’ve ever watched. And yes, I cried. (I’ve come to realize I’m a sucker for movies about old people and/or death.) When Haskell meets with his ex-wife, who is Mark’s mother, she is at a nursing home for Alzheimer’s patients. I wasn’t sure that she remembered him until he begins whispering to her about how everyone has secrets. It is then that she says “I know” and he shows real emotion and begins to cry. This moment is the moment that Maysles speaks about when the subject of a documentary stops acting. Without this scene, this film would be pointless and inauthentic. While most of the film feels like an amateur documentary with no inspiration, for this one moment, Mark is able to take his father’s advice and instead of trying to tell the viewer what is going to happen, simply sit back and observe a heartfelt moment of humanity.